Kuki-Zomi women have left home to protect the homeland. They’re patrolling the ‘frontline’

Don't Miss

- Agitating Ladakh leaders allege attempts by UT administration to sabotage their talks with centre

- Women dismantling unfair barriers, not intruding professional spaces: Supreme Court

- India on Edge as China-Bangladesh Defence Ties Deepen: Lalmonirhat Airbase Near Siliguri Corridor Raises Strategic Alarm

The ethnic conflict that’s ripping Manipur apart is changing the rules of the tight-knit patriarchal Kuki-Zomi society. Now, the women are protectors, protesters and planners.

|

| Kuki-Zomi women stand on the main road so that they can protect the women sitting at the protest site | Photo: Manisha Mondal | ThePrint |

She’s barely five feet, and unarmed, but that doesn’t stop her from standing in front of the van and glaring at the driver through her photochromatic glasses. The driver, his face stuffed with paan laughs at her, but he and the others soon learn that the women mean business. No unauthorised vehicle will pass through their checkpost into the safe zones without their say-so. They’re protecting their children, parents, friends and husbands.

Ever since violence erupted between the Meiteis and Kuki-Zomi in May 2023, the women of the tribal community have stepped out of their homes and traditional roles as caregivers for their husbands, brothers, children, fathers and extended family members. Now, they are defenders, peacemakers, accountants, planners and organisers. Hands that crushed garlic and fermented fish in the kitchen are now handling guns, forming human chains, staging protests, running checkposts and volunteering at the frontline—along with their regular household duties. It’s a movement led by women’s organisations at the grassroots level, which flies in the face of tradition.

“The violence triggered us to come out, not one, or two, but lakhs of us,” says one of the women with Mercy. The ethnic conflict that’s ripping Manipur apart is also changing the rules of their tight-knit patriarchal society.

Women opens the boxes at the check point for checking | Photo: Manisha Mondal | ThePrint

Women inspect boxes at the checkpoint | Photo: Manisha Mondal | ThePrint

“It’s not just our loved ones, but our homeland, our way of life, that is at stake. We have left our duties as wives and mothers so we can be here for our homeland,” says Mercy, as she and other women at the check post efficiently register the Aadhaar card details of the drivers and licence plate numbers, and search the betel leaf loads before allowing the vans to roll into the Kuki-Zomi dominated district.

Around 200 Meiti and Kuki-Zomi people have been killed in the ethnic violence in Manipur, which shows no sign of abating. Over the last nine months, civilians have used sophisticated weapons like assault rifles and machine guns in the conflict.

“The time and conditions have compelled us to come out. We have Kuki-Zomi women holding guns at the duty posts for our homeland. It is a drastic change in our history”, says Nu Ngaineikim Haokip, general secretary of Kuki Women Human Kuki Women Organisation for Human Rights.

Protectors, agitators, instigators—their role in this conflict is defined by who you ask—their loved ones or the police.

|

| Women gather for brunch at the checkpost | Photo: Manisha Mondal | ThePrint |

Teachers, mothers, wives and guns

On a cold wintry morning with no sight of the sun, Mercy waves goodbye to her 13-year-old daughter, stops by to talk to her mother who runs the family’s small medicine and grocery store, and takes an auto to the duty checkpost, some three kilometres away. Her daughter will cook for the family before going to school.

She has weekly shifts from 6 am to 4 pm, but if the situation escalates, then her hours are extended.

The days are long and gruelling, but Mercy—whose father is the Tuijang village chief—does not regret her decision to leave Chennai and return to her family home to help her brother and mother. That was in 2018; the last few months have shredded their quiet way of life.

Both the checkposts bordering Churachandpur district at Kawlian and Kaprang are operated by Kuki-Zomi women. The makeshift posts made of hay, grass and soil offer little protection from the biting cold, harsh winds or the glare of the afternoon sun. Women, mostly housewives, living in the border villages of Churachandpur take turns to volunteer at the duty posts.

What was once an oddity in their routine has become the new normal. Even the regular drivers have learned to respect this crack team of women volunteers. “Sometimes they do not take us seriously, but we have to be serious and persistent,” says Kima Khongsai, another village volunteer.

All the women are unarmed—they don’t even have batons or bullhorns. But they can run behind vehicles, shouting at the top of their voice. It works, the women say proudly.

“We have to keep a check on drugs or any other illegal substances being traded through this route, it is our job nowadays to be vigilant,” says Mercy.

But what nobody talks about is how almost everyone is trained to handle guns. Village defence committees have sprung up across Manipur— even in villages in the Meitei-dominated valley of Imphal —where volunteers are trained at the community level. Around 30 per cent of tribal women now know how to use a single-barrel gun, according to the women’s cell of the Indigenous Tribal Leader’s Forum.

While Mercy and other village women volunteers are at the border, 28-year-old Julie is getting ready for her shift at the Indigenous Tribal Leader’s Forum office in Churachandpur. But first, she has to see to her charges at Young Pillar School where she teaches in the mornings.

|

| Julie carries two kids in the school courtyard | Photo: Manisha Mondal | ThePrint |

Soft-spoken with kind eyes, Julie carries two pre-primary children in her arms, while playing with 10 others. When she enters the tiny classroom with a partially decorated Christmas tree in the corner, the children run to her. “ Ma’am, Ma’am,” they vie for her attention.

By 1 pm, she gets ready to leave the school and take command as the information secretary at the Indigenous Tribal Leader’s Forum (ITLF) office.

Women at the ITLF office | Photo: Manisha Mondal | ThePrint

“I have visited almost every frontline to distribute food items, medicines and sanitary supplies. We, the Kuki-Zomi women, have taken up these responsibilities. We negotiate with men in uniform if they try to catch our men volunteers,” she says as she revs her scooter.

She gently evades questions on whether she can handle a gun.

“I do not need a gun, my voice is enough”.

‘These are our hills’

By the time Julie reaches the ITLF office, it’s teeming with women volunteers who have gathered for a meeting. It was a day before the Kangla Fort meeting where the radical armed Meiti group Arambai Tenggol had summoned two MPs and 37 MLAs of the state.

As women filter in, laughter fills the room. They exchange news, village gossip and “developments in the valley” (Imphal).

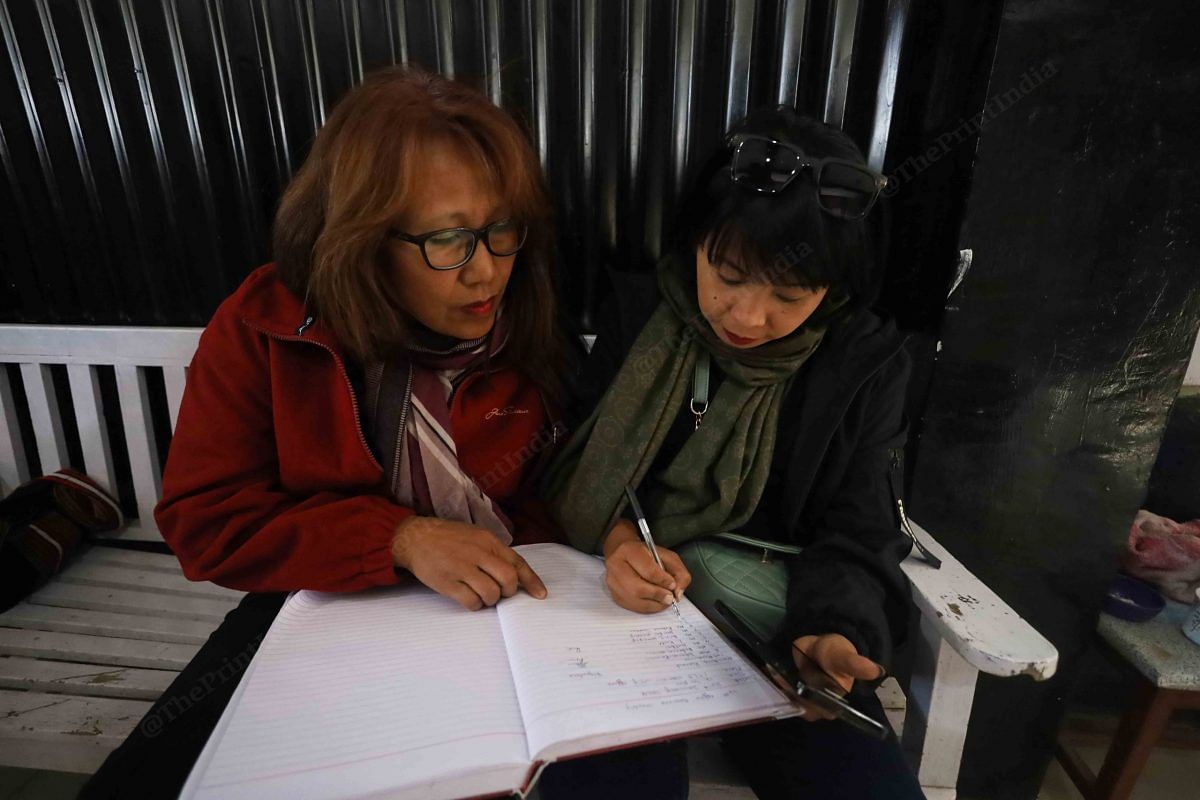

At the ITLF office women sign registers | Photo: Manisha Mondal | ThePrint

|

| Women at the ITLF office | Photo: Manisha Mondal | ThePrint |

“She is the strongest among us, she is just a little tired because of all the work,” says Rebecca. In her 50s, with her no-fuss bob cut, she has an air of calm authority.

She’s one of the few women to have rebelled against conservative mores of tribal society. She’s ridden bikes, driven a Mahindra Thar SUV on solo adventure trips, and now she’s the woman others look up to as violent change sweeps through their society. She also happens to be a licensed gun owner, who is now training other women to aim and shoot.

Every day, after finishing her household chores and taking care of her family, she hops into her Thar, to the frontline delivering medicines or carrying out routine checks. At other times, she’s either at the ITLF office or HWA headquarters attending meetings, discussing future plans, tactics and practising at gun targets.

“We will not kill any women or children using our skills, we want to defend ourselves,” says Rebecca.

A Sunday afternoon finds her on a 45-minute hike to the peak of a Samulamlan village hill to deliver “necessary items” to Kuki-Zomi volunteers for when they come face to face with the army men from the Mahar regiment.

“The situation of hill districts was getting better in the past few years, but we have gone back to square one,” she says. No one knows how it will all end. Accusations that the Kuki-Zomi are outsiders, not Indian, hurt. This is her home, the only one she knows.

“It is not easy to be called a narco-terrorist, an illegal immigrant, even when we were born here in this part of India,” she laughs.

|

| Teresa on the way to deliver items to Kuki-Zomi volunteers | Photo: Manisha Mondal | ThePrint |

While on her way, she stumbles upon a group of eight-10 Indian Army soldiers in green fatigues. Unfazed by their presence, she wipes the surface of a tree trunk and takes a seat as the soldiers load their guns.

“These are our hills,” she says calmly pointing towards the Kuki-Zo-dominated area. “The volunteers stationed here are protecting our villages from Meiteis.” Her voice is low. The soldiers agree to leave, and she leads them to the buffer zone away from the villages.

“I know they are here to remove the duty post. This hill does not come under their jurisdiction, and they should not be here,” Rebecca says in Hmar dialect to her close friend Teresa who has accompanied her on the hike.

The sun is starting to set, and Rebecca stops to stare down at the lights at Churachandpur city flickering from a distance.

“It’s been nine months and I have not had quality time with my family,” she says as she gets a call from home for dinner. “I have to go home, they are waiting.”

A woman volunteer cooks chutney | Photo: Manisha Mondal | ThePrint

A new feminism

If home is where the heart is, then the women in border villages are the heart of this movement. The villages are where volunteers meet, rest, eat and plan. The women of the village cook in shifts. In New Zalenphai village, the chief’s wife Bethany Pouthang is always at the centre of the activity. Big, loud and proactive, she’s everywhere. Not only does she teach at a local school, she oversees the women volunteers in the village, their shifts, the menu for the day and liaises with other village volunteer groups.

Like Mercy and the guards, she never leaves the house without bright lipstick and sports shoes.

Her husband, the village chief Ngamkhopao Haokip stays with the volunteers while Bethany often travels from the city to the village for errands. The 10-km ride can take as long as 45 minutes because of the bumpy roads.

Before leaving for the ‘frontline’, she runs through the dinner menu—dal, rice and chutney with fermented fish—and speaks to some of the village women.

|

| Villagers bring food for the women who are stationed at the checkpost | Photo: Manisha Mondal | ThePrint |

“We are burdened with work, but right now, we need all hands on deck,” she says. As the car starts moving forward, Bethany shouts “Stop, stop! My son, My son.”

She’s spotted her 10-year-old son Seiminhao returning to the village riding pillion on a friend’s scooter. He’s supposed to be in Churachandpur with his aunt. He hadn’t informed her of his little jaunt. Furious, Bethany drags the boy into her car.

“These kids are unaware of how critical the situation is right now. I have told him so many times not to visit these areas without my permission,” Pouthang takes a long breath.

She’s trembling with rage. Later, when she reaches the ‘frontline’, she points towards a green roof across the paddy fields. “That’s the Meitei area. That’s where they fired at us a few days ago [early January].”

She doesn’t want her children in the firing line.

|

| Kids walk around with sticks at the border areas | Photo: Manisha Mondal | ThePrint |

“It has been difficult for us to manage so many duties at the same time. Since May, I have not been able to take out time for my kids. My sister has been taking care of them,” says Pouthang.

According to Nu Ngaineikim Haokip, general secretary of Kuki Women Human Kuki Women Organisation for Human Rights (KWOHR), the tribal society has always been patriarchal. Decisions were always made by the men—even when they adopted Christianity

But over the recent years, this has slowly changed through activism and awareness about women’s rights. The ethnic conflict has galvanised this movement.

“The graph of improving conditions of Kuki-Zomi women has been slowly and steadily growing. However, it reached its peak with the violence last year. In the past when there have been any situations women have stepped out of their homes protesting. But this is the first time there are Kuki-Zomi women volunteers out there in the frontline,” says Haokip.

The urgency and tension are layered with an undercurrent of pride in what they have achieved.

“Tribal women, who are always seen only as the caregivers, have shown the world how strong and determined we can be,” says Lalam Haokip, president of Kuki Women Union.

|

| Women protesters board small trucks as they leave after the protest | Photo: Manisha Mondal | ThePrint |

We are not aggressive

Every Wednesday, thousands of women dressed in black gather at the Wall of Remembrance just outside the Mini Secretariat in Churachandpur city for a peaceful sit-in protest. It’s a ritual to show solidarity, grieve and demand justice.

The usually quiet town is transformed as tempos filled with women rumble in. There is no sloganeering, rather they sing prayers and listen to the speeches by the women leaders. The young and the old, the married homemakers and the working women—all leave their work and chores to join the protest which starts at 11 am and wraps up by 2 pm.

The women make sure that ambulance and defence troop movements are not obstructed.

Gracy Vaiphei (name changed), PHD student and a resident of Churachandpur, looks on in wonder. She’s never seen anything like this before.

“I do not know if this is a global phenomena, or this crisis that has triggered this. We did not know how to do dharna [protests] but it has changed. Women’s participation has increased. This is a new beginning,” Vaiphei.

A few women set up benches as roadblocks and sit patiently listening to the women speakers, exchanging bits of information.

“Meira Paibis blocked the highway again,” says one woman. The other women snicker. Kuki-Zomi women function differently than the Meitei Meira Paibis—the ‘women torch bearers’ named after the flaming torches they hold while marching in the streets, often at night. They are guardians of society fighting alcohol and drug abuse among men.

But their role as the mother and protector of society was questioned when the Kuki-Zomi community alleged that there the instigators behind some of the rapes and violence against them.

|

| A woman protester prays during the weekly protests | Photo: Manisha Mondal | ThePrint |

The women at the protest site don’t want their newfound movement to be associated with the Meira Paibis.

“They are so aggressive; they shout. Do others think we are like them? Do they judge us because of how we are protesting? Please do not judge us…when we are singing, this is how we protest,” says another woman.

In July 2015, around 12 Meira Paibis women stripped in front of the Kangla fort, holding a banner that read ‘Indian Army Raped Us’.

“We are different from Meira Paibis. Kuki-Zomi women are conservative, we will never take our clothes off. If anybody wants to kill us, we will die with our clothes on,” says Nu Ngaineikim Haokip.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

.png)

0 Response to " Kuki-Zomi women have left home to protect the homeland. They’re patrolling the ‘frontline’"

Post a Comment

Disclaimer Note:

The views expressed in the articles published here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position, or perspective of Kalimpong News or KalimNews. Kalimpong News and KalimNews disclaim all liability for the published or posted articles, news, and information and assume no responsibility for the accuracy or validity of the content.

Kalimpong News is a non-profit online news platform managed by KalimNews and operated under the Kalimpong Press Club.

Comment Policy:

We encourage respectful and constructive discussions. Please ensure decency while commenting and register with your email ID to participate.

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.