Sikkim's war on GLOF. Monks, shamans, and scientists are all in the fight

Don't Miss

Sikkim's South Lhonak glacial lake outburst flood killed 90 people in 2023. Villagers are angry and the state government is wary of attributing the GLOF to climate change—Rs 2,500 crore insurance claim is at stake.

Soumya Pillai, The Print, from Gangtok, Dzongu, and Chungthang, Produced by Soham Sen: It took a year after the disastrous Teesta River flooding for the first multi-agency expedition team to reach and study the melting glaciers in Sikkim. When they arrived, they were met with angry tribals wielding sticks and stones.

“Where were you when we were rebuilding our villages? The government was nowhere. But now you need our help,” a team member—a senior geologist—recalled the flurry of angry questions from the villagers.

Sikkim is spearheading the Centre’s plans to counter the impact of climate change and make it a lesson to study the glacial lakes across all Himalayan states in the country. But the team needed the participation of the community—to access Khang Chu glacial lake, record their findings, and develop concrete disaster mitigation solutions such as early warning systems, anti-encroachment drives, and awareness campaigns.

On paper, it sounded simple enough. But the expedition team had to face many obstacles: a human wall blocking the road, broken trust between the government and villagers, and the belief that the gods were angry. It took three days, two monks, Sikkim’s chief minister, and multiple rounds of talks with two Pipons—the heads of the communities—to reach an agreement. The team would be allowed to study the glacial lake under strict supervision and with several restrictions.

“Until now, we [have] relied on satellite images of these glacial lakes, but to have an implementable plan of action, we need to reach these lakes and note the changes they are experiencing [due to] climate change,” said Prabhakar Rai, director of the Sikkim State Disaster Management Authority (SSDMA), one of the government agencies participating in the expedition.

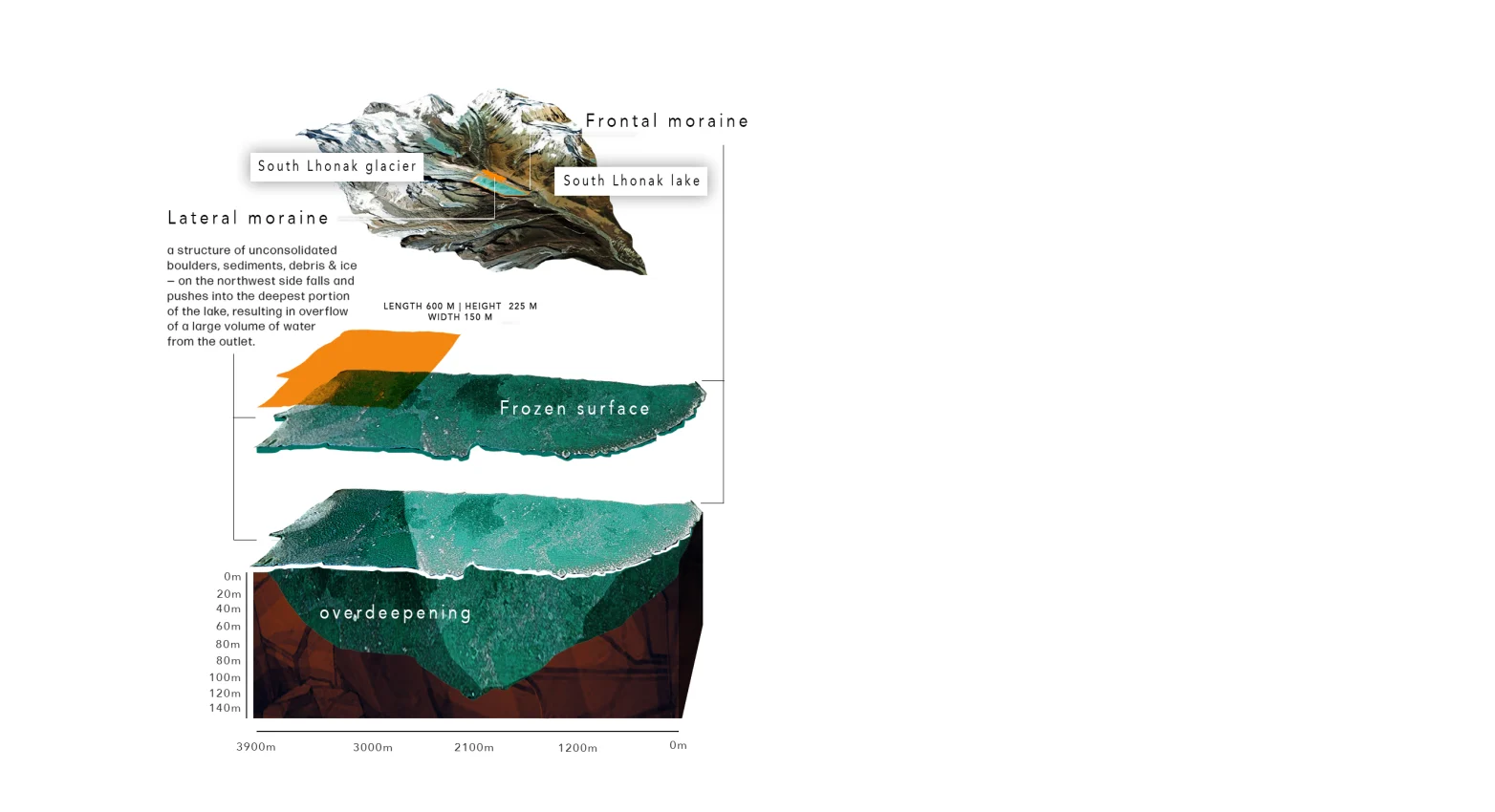

Scientists, who will submit the findings to the Sikkim government in October, have observed a worrying trend of climate change-driven warming of the glaciers. The expedition team discovered that Lhonak Lake breached its embankment following an avalanche on the surrounding mountains, causing icecaps and sediments to roll into the lake and displace water that gushed down the valley.

The Sikkim government, however, is wary of attributing climate change as a possible cause of GLOF events. It is contesting a central committee report that blames GLOF for the incident, arguing instead that it was caused by a cloudburst. What’s at stake is a Rs 2,500 crore insurance claim.

Lhonak Lake has well-marked passages around it, ensuring that water is released in a controlled manner, explained one of the team members. If a similar breach happened in any other glacial lake, the force of the released water would be much greater.

“The 2023 glacial lake outburst flood was not the first such disaster in Sikkim, and [they] will not be the last. In fact, such episodes will only become more frequent now,” said Rakesh Ranjan, head of the geology department at Sikkim University.

The 'crying wolf' alarm

A few months before the disaster, Sikkim authorities initiated a pilot project for an early warning system in Chungthang district, where the dam broke. Whenever water breached a certain level in the dam, alarms would wail—a sign for residents to evacuate.

However, “alarm fatigue” soon set in due to the repeated mock drills.

“They [alarms] would go off a few times every week during the monsoon season when water reached a certain level in the dam. It became routine for us, and we stopped caring,” said Tenzing Bhutia, a resident of Chungthang town.

What nobody had told the villagers was that the system was still being developed.

On the day of the disaster, about 20 minutes before floodwaters overwhelmed the village around midnight, the alarms went off. Nobody believed them. It was the boy crying wolf all over again.

Samdup Lepcha, 45, from the Affected Citizens of Teesta, a citizens’ group in Sikkim, said that many village elders did not leave their homes, thinking the blaring alarms were part of routine drills.

“They were confident that even if the dam water breached the danger mark, it would never impact them. By the time they realised the gravity of the situation, it was too late,” Lepcha said.

Chungthang town was the first to be hit when the 1200-megawatt Teesta Stage-III Hydropower Electric Project dam collapsed. Villagers recalled that heavy rains had caused a power cut, which wasn’t unusual. Then they heard the water. The tempo of the Teesta’s flowing water turned from a musical gargle to a violent roar. The water crashed against the banks, and houses vanished in seconds.

|

| A house that was damaged in the 2023 GLOF | Photo: Soumya Pillai | ThePrint |

According to state authorities, if the early warning system had not been activated that night—even in its partial form—Chungthang could have faced a much greater tragedy.

“Lives were saved because of the timely alarms. Over the past few months, residents were trained to respond to emergency alarms...to evacuate and were informed about safe routes and shelters. The system was not fully functional, but it did help,” a state disaster management authority official told ThePrint.

The villagers, however, are not convinced. They view this as a frail attempt by the government, and argue that the time between the alarm and the water reaching their village was not enough for safe evacuation.

State government proposals and simulations conducted by scientists in Sikkim show that when fully operational, the early warning system could provide at least 90 precious minutes for villagers to evacuate. A fully functional warning system is expected to be implemented in Chungthang by 2025, with similar projects planned for 16 high-risk glacial lakes over the next five years.

At the national level, the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) has prepared a broader plan to undertake expeditions to 189 high-risk glacial lakes across four states—Sikkim, Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Uttarakhand. A sum of Rs 150 crore has been approved under the government’s National Glacial Lake Outburst Floods Risk Mitigation Programme (NGRMP) to study these lakes.

0 Response to "Sikkim's war on GLOF. Monks, shamans, and scientists are all in the fight "

Post a Comment

Disclaimer Note:

The views expressed in the articles published here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position, or perspective of Kalimpong News or KalimNews. Kalimpong News and KalimNews disclaim all liability for the published or posted articles, news, and information and assume no responsibility for the accuracy or validity of the content.

Kalimpong News is a non-profit online news platform managed by KalimNews and operated under the Kalimpong Press Club.

Comment Policy:

We encourage respectful and constructive discussions. Please ensure decency while commenting and register with your email ID to participate.

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.