CAA comes not with a bang, but with a whimper. Without NRC, it will fade into academic debate

Don't Miss

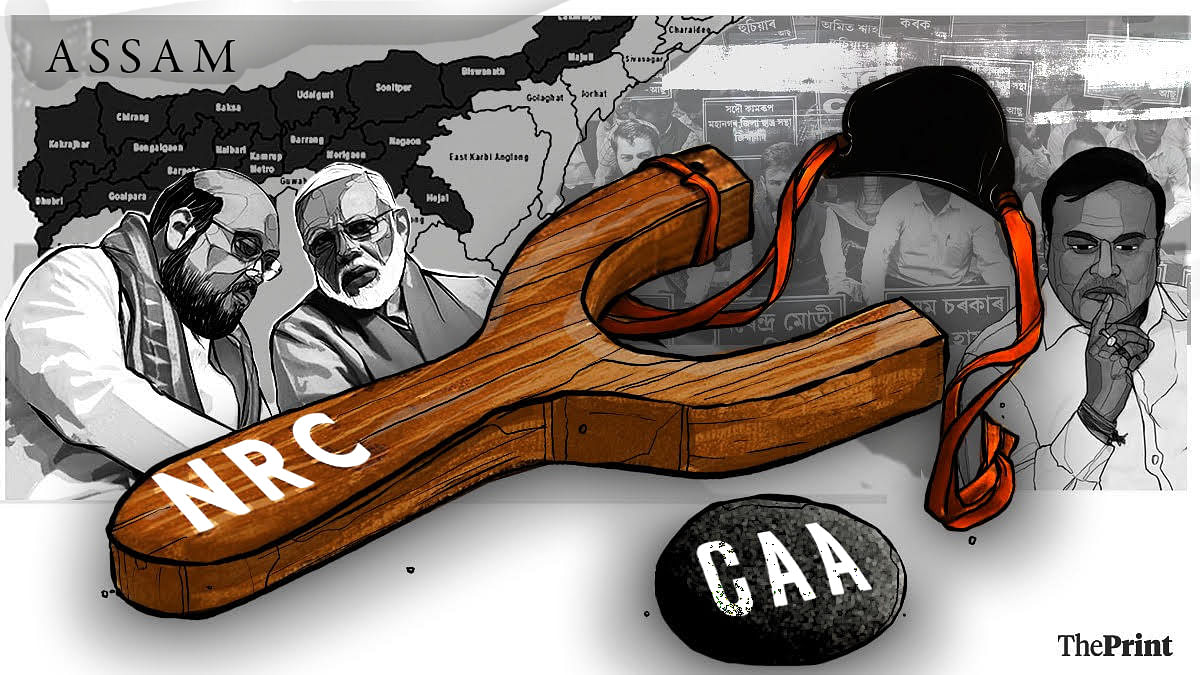

For BJP, CAA was strategic move that did not quite work out because those it would benefit could’ve been accommodated under existing laws, and new entrants would remain excluded.

SHEKHAR GUPTA, The Print, 16 March, 2024 : The Modi government’s notification of the rules of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA), it seemed, had failed in the immediate purpose of its timing: overshadowing the Supreme Court order on anonymous electoral bonds. The bonds story had fuel to last.

The CAA was dying out. Until two things happened. One, Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal attacked the law as an invitation to millions of poor and unemployable “illegal immigrants and ghuspethiyas (infiltrators)” from Pakistan and Bangladesh. This sparked protests outside his house by hundreds of Pakistani Hindus currently living in inhuman conditions in illegal bastis in the capital.

An even more important role was played by the US State Department in bringing the story back into the headlines, at least below the fold as we would say in old newspapering parlance. Spokesman Matthew Miller said at his usual briefing that the US was concerned by the law, stood by equity for all faiths, and was making a close study of it.

At which point I shall make a humble request to him and his principals at the State Department: If after the deepest study you do indeed figure out what you find wrong with this, please do also let us know in India. Or, as Kishore Kumar sang in Majrooh Sultanpuri’s words for Dev Anand in his 1965 classic Teen Deviyaan: agar tumhi samajh sako mujhe bhi samjhana.

Forgive my lapsing into the old Hindi film nostalgia. The fact, however, is that on the closest study, I find it difficult to decide whether the CAA, as it reads now with its rules, is good, bad, a bit of both, or inconsequential. Let’s try and examine this from the point of view of its likely — or intended — beneficiaries, victims, and the ones with principled arguments.

• The most likely beneficiaries are mostly Hindus, some Sikhs, Christians and probably a few Buddhists in Pakistan and Bangladesh. Precise figures are hard to come by, though unlike India lately, Pakistan had a census in 2023. Let us say, for ease of understanding, that the number is about two crore, more than 95 percent of them Hindu. Presuming that most or any of them feel dreadfully persecuted and want to come to India, won’t they be jumping in joy at the CAA?

The answer, unfortunately, is no. They are 10 years too late. The law would have benefited them only if they had come to India by the end of 2014. Because 31 December, 2014 is the cut-off for its application.

• This is a bummer, but surely those who came before 2014 will now benefit? Yes, but they can also ask a question: If India, especially under the Narendra Modi-led BJP government, really felt so strongly about them, why did it not give them citizenship in all these 10 years? The Government of India has the sovereign power to accord citizenship to anybody. It doesn’t need any special law for any community. Surely, no new law was needed to give Indian citizenship to singer Adnan Sami, which was done with some fanfare on camera by then minister of state for home affairs Kiren Rijiju.

Why make us, the poorest and most miserable Hindus from Pakistan and Bangladesh, live in subhuman conditions as illegal immigrants for all these years? Were we then made to wait 10 extra years for a more opportune moment in the BJP’s politics?

• With the likely beneficiaries out of the way, we come to those fearful of it. Why is there no Shaheen Bagh-style stirring now? It is because the cause for action in 2019 doesn’t exist now. Then, the CAA was following a widely proclaimed chronology that would have seen a nationwide National Register of Citizens (NRC) process in its wake. The fear of the NRC was buried, even ridiculed by Prime Minister Modi himself in his speech at Ramlila Maidan on 22 December, 2019. There was obviously a realisation that the party had gone too far. This was an absolute no-no when the prime minister was taking such pride in receiving the highest national awards from the key Islamic countries and understood the value of his new relationships in the Arab Middle East, outflanking Pakistan. Since then, no BJP leader has resurrected it. If there is no NRC, no Muslim in India has to fear anything.

• The only part of the country where the law makes a difference is Assam. Successive amendments to Indian citizenship law have maintained the Assam exception. That’s in deference to the anti-illegal immigration (later renamed anti-foreigner) mass movement in the state from 1979 onwards. The native Assamese speakers of the Brahmaputra Valley and tribal areas believe that tens of millions of Bangladeshis illegally settled in their state, upsetting the demographic balance. The RSS has campaigned for more than four decades in the state to convince the Assamese Hindus that they should make a distinction between Bengali Muslims and Hindus. That was successful, but never fully.

The difference in Assam is that an NRC process had already been carried out there. Assam got caught in a twin trap. First, the NRC caught too many Hindus as aliens. Despite the rise of the BJP/RSS, a large enough number of Assamese, especially the students, still won’t make an exception for Bengali Hindus. That is the reason Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma is now trying to douse the fresh unrest by arguing that the idea that millions or lakhs of Bengali Hindus will now be naturalised is ridiculous. If at all, it will be “50-80,000 people (Hindus)” in the Barak Valley, he says. If these are all the people this politically disruptive law might benefit, you might ask why it was even needed.

It would be reasonable to conclude that for the BJP, it was a strategic move that did not quite work out because those it would benefit could easily have been accommodated under the existing laws, and new entrants would remain excluded. The hope of nationwide polarisation and street unrest vapourised with the PM himself taking the NRC out of the game.

The Muslim community has also displayed a shrewd, underdog’s maturity in not reacting to the latest development. Principled, constitutional arguments on whether the state can define citizenship based on faith will continue to be made in the Supreme Court. Whatever the verdict, it will be academic and make no substantive difference.

There will be some noise and ceremonial handing over of citizenship certificates. Beyond that, the CAA story lies defeated by the haste and political miscalculation behind it. It can only revive if one or both of the following happen: fresh talk of a nationwide NRC and/or the cut-off date being shifted forward from 31 December, 2014. Can it happen? I’d suggest watching this space in the run-up to 2029.

0 Response to "CAA comes not with a bang, but with a whimper. Without NRC, it will fade into academic debate"

Post a Comment

Disclaimer Note:

The views expressed in the articles published here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position, or perspective of Kalimpong News or KalimNews. Kalimpong News and KalimNews disclaim all liability for the published or posted articles, news, and information and assume no responsibility for the accuracy or validity of the content.

Kalimpong News is a non-profit online news platform managed by KalimNews and operated under the Kalimpong Press Club.

Comment Policy:

We encourage respectful and constructive discussions. Please ensure decency while commenting and register with your email ID to participate.

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.