What is the Data Protection Bill of 2023?

How is the Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2023,

different from its previous iteration? What are the domains

where it has made advances and the ones where it is lacking?

The story so far

The journey towards a data protection legislation can be traced back to 2017 when an expert committee was constituted by the Ministry of Electronics and

Information Technology (MeiTY).

The

major development came in December

2021 when the Data Protection Bill,

2021 (DPB, 2021) was released.

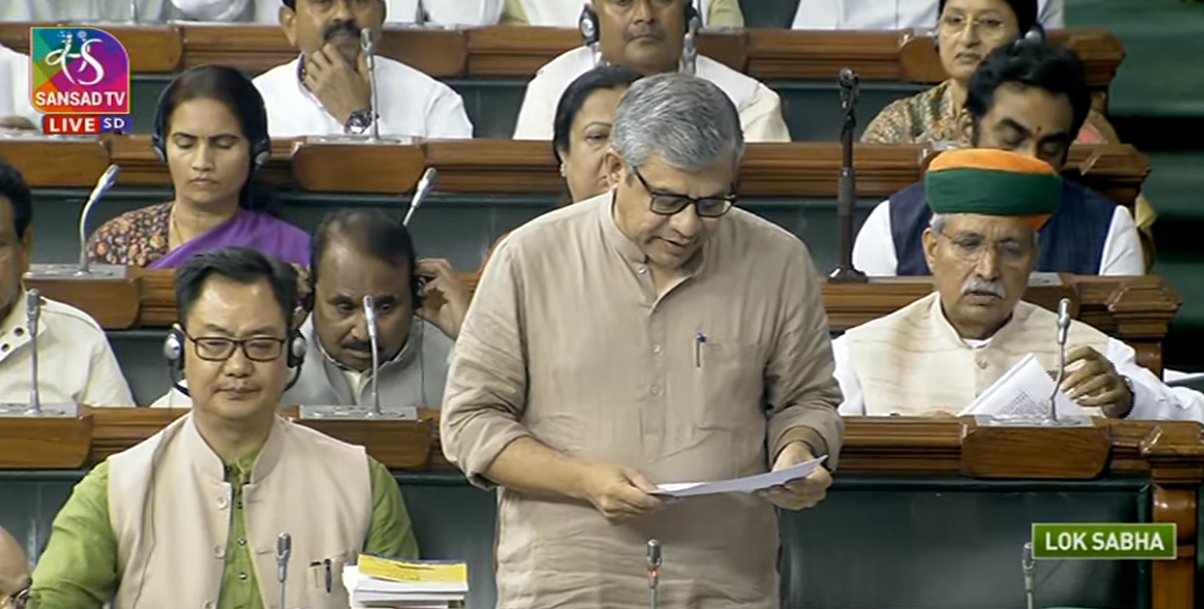

However, it was withdrawn in

Parliament by Minister for

Communications and

Information Technology

Ashwini Vaishnaw on

August 3, 2022. On

November 18, 2022, a draft of

the Digital Personal Data

Protection Bill, 2022 (DPDPB, 2022)

was released for public consultation.

The submissions made under this consultation process were not made public.

The request to publicly release the sub-

missions was also denied in a Right to

Information application. One year on,

the 2023 Bill has been tabled in

Parliament without clarifying how and

on what basis these changes were incorporated.

Who does it protect?

In a first, the new Bill introduces duties

and penalties on a data principal (DP).

Clause 11 of Chapter III states that the

DP has the right to request from the data

fiduciary (DF), a summary of the personal data being processed, identities of all the DF with whom

its personal data has been

shared and so on, subject to a

few exceptions. under

Clause 12, users can seek correction, completion, update and

erasure of their personal data.

Interestingly, the provision which

allowed a DF to reject this request has

been removed. users have also been

given the right of grievance redressal

(Clause 13) and the right to nominate

another individual in the event of death

or incapacity to exercise their rights

(Clause 14).

While the impetus for a data protection legislation must be to protect a DP's personal data from being

unwittingly exploited, the Bill

appears to be designed in a manner

that this protection is compromised.

Interestingly, the Bill further goes on

to impose duties and penalties on the

DP.

To exemplify the above, Clause

15(d) of this chapter states that the

DP must ensure not to register a false

or frivolous grievance or a complaint

with a DF or the Data Protection

Board (DPB), and failure to adhere

with this may enable a penalty of

`10,000 (Chapter VIII). This is an

onerous obligation which may effectively prevent a DP from raising

grievances.

Who does it exempt?

Data breaches are becoming regular

occurrences.

It was reported in June

2023 that a major privacy breach

with respect to the CoWIN portal

had taken place and personal details

of vaccinated users had been leaked

on Telegram. Recently, in July 2023,

about 12,000 confidential records of

State Bank of India employees were

reportedly made public on Telegram.

In view of this, a cause of great concern that arises in the Bill is the

exemption under Clause 17(2)(a)

which, if notified, is granted to the

government and its authorities.

On five specified grounds, the

Bill exempts government authorities,

as notified, marking a discernible

expansion of the scope of exemption.

Personal data which is

processed for research, archiving, or

statistical purposes will also be

exempted under Clause 17(2)(b).

While previous iterations of the

Bill also provided exemptions, this

has now been broadened to state that

data processing undertaken by the

union government on information

provided to it by an exempted instrumentality will continue to remain

exempted from the purview of this

law.

What does it seek to amend?

The changes that the Bill seeks to

implement by way of Clause 44 are

significant. For instance, Section

43A of the Information Technology

Act, 2000 (IT Act) imposes an obligation on corporates to award dam-

ages to affected persons in case of

negligent handling of their sensitive

data. Clause 44(2) of the Bill aims to

exclude the application of Section

43A, thereby rendering an individual

who has suffered breach of their data

without any relief.

Clause 44(3), which seeks to amend the entire Section 8(1)(j) of

the Right to Information (RTI) Act,

2005 and replace it with "information which relates to personal information", has received heavy criticism from stakeholders. Previously,

qualifiers existed which narrowed

the information that could be with-

held by the public information officers. Now, the removal of "has no

relationship to any public activity or

interest, or which would cause

unwarranted invasion of the privacy

of the individual" widens the scope

of withholding information.

Does it protect users?

A widely appreciated departure from

the previous iterations is the DF's

obligation to notify the DP in case of

personal data breach. Other obligations imposed on DF include notifying the DP about the purpose for

which their data may be processed,

and the manner in which they may

make a complaint to the DPB, with-

draw consent, and seek grievance

redressal.

However, as discussed before,

there is a deviation from DPB 2021

with removal of the provision for

compensating a user affected by personal data breach. In further departure, Clause 5, which outlines notice

obligations on DF does not mandate

them to inform DPs about data being

shared with third-parties, duration of

storage of data, and transfer of data

to other countries.

Lack of obligation

on the part of DF to notify DP at the

offset makes the DP's right to obtain

information pertaining to their personal data perfunctory.

"The assumed consent frame-

work of DPDPB, 2023, on the other

hand, remains unchanged. In place

of using the term "deemed consent",

which was present in DPDPB, 2022,

Clause 7 uses the term "certain legitimate uses", which outlines the various situations in which personal data

may be processed without obtaining

the DP's informed consent.

The

DPDPB, 2023 fails to differentiate

between "personal data" and "sensitive personal data", consequently

negating the elevated level of protection associated with the latter."

Chapters V and VI deal with the

DPB which is the primary authority

for ensuring that DPDPB, 2023, is

upheld. DPB's independence has

also been in question since the 2019

version. DPDPB, 2023, mandates all

its members to be appointed by the

union Government. A favourable

evolution is the clarification that

salary, allowances, and other terms

of service of DPB members cannot

be varied to their disadvantage post

appointment. However, only adjudicatory and not regulatory powers

have been bestowed upon the DPB.

0 Response to "What is the Data Protection Bill of 2023? "

Post a Comment

Disclaimer Note:

The views expressed in the articles published here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position, or perspective of Kalimpong News or KalimNews. Kalimpong News and KalimNews disclaim all liability for the published or posted articles, news, and information and assume no responsibility for the accuracy or validity of the content.

Kalimpong News is a non-profit online news platform managed by KalimNews and operated under the Kalimpong Press Club.

Comment Policy:

We encourage respectful and constructive discussions. Please ensure decency while commenting and register with your email ID to participate.

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.