Deconstructive Praxis and the Politics of Independence

Yanis Iqbal, Countercurrents, 15 August 2023 : On August 15, 2023, India will celebrate its 77th Independence Day. However, back in 1947, Tamil Nadu saw this day marked by black flags and black shirts. For Periyar, political independence meant a transfer of power from the “British to the Brahmins and Baniyas”. Instead of examining the entire Indian landscape from the perspective of rationalist-revolutionary politics, upper-caste ideologues limited the upheaval of the nationalist movement to the goal of removing colonial power. Swaraj took on a spiritual significance, neglecting vital social aspects like caste, untouchability, gender, and class. The dogmatic boundaries of independence were formed on the shores of religious normativity, which replaced the open-ended exploration and transformation of reality with unyielding faith in an absolute ideal. Drawing these parallels between the discursive structure of nationalism and religion, Periyar remarks:

“Those who call this nation an independent nation can only be those nationalists and others for the sake of their daily bread and because of the greed for power and status. Can an honest individual who is part of society say such a thing today? At this stage this country has millions of gods and goddesses, hundreds of temple festivals, marriages of the gods, elaborate worship rituals five times a day or more. All of these continue unabated. In that case is this nation ruled by people or by ghosts, non-human entities? We should think about whether this country has freedom or an unflinching domination of slave-like thinking.”

Servitude arises when our purposes gain a measure of autonomy and start dictating our own actions. Independence becomes an unquestionable abstraction whose fixity fanaticizes us, instead of serving as a mere object for our own self-determination. How do we overturn the fetishized independence of India’s Independence Day? By consuming it. According to Jacob Blumenfeld’s unique interpretation of Max Stirner’s philosophy, consumption names process whereby an “owner abolishes the separated power of the object of property.” As a form of relation between the subject and the object, it is the dynamic that dissolves the external character of ideas, relations and objects, thus absorbing “them into one’s power as property to be used and abused at will.” Property is inherently bound up with the logic of occupation, expropriation, and negation. To own is effect force in relation to things or persons. By misusing, infringing upon, and destroying property, we can ascertain whether I own the property or if the property owns me. Unveiling the true owner of property is accomplished by its destruction (consider, for instance, Periyar’s breaking of Ganesha idols as part of protest). In the words of Blumenfeld: “When workers go on strike and destroy their own tools, when youth riot, burn their own neighborhoods and loot their own stores, when students occupy their own universities and render them inoperative, it is an assertion of ownership over the property in question, an assertion of power that validates the criteria of who and what rules. If a thing cannot be nothing to me, then it is not properly mine.”

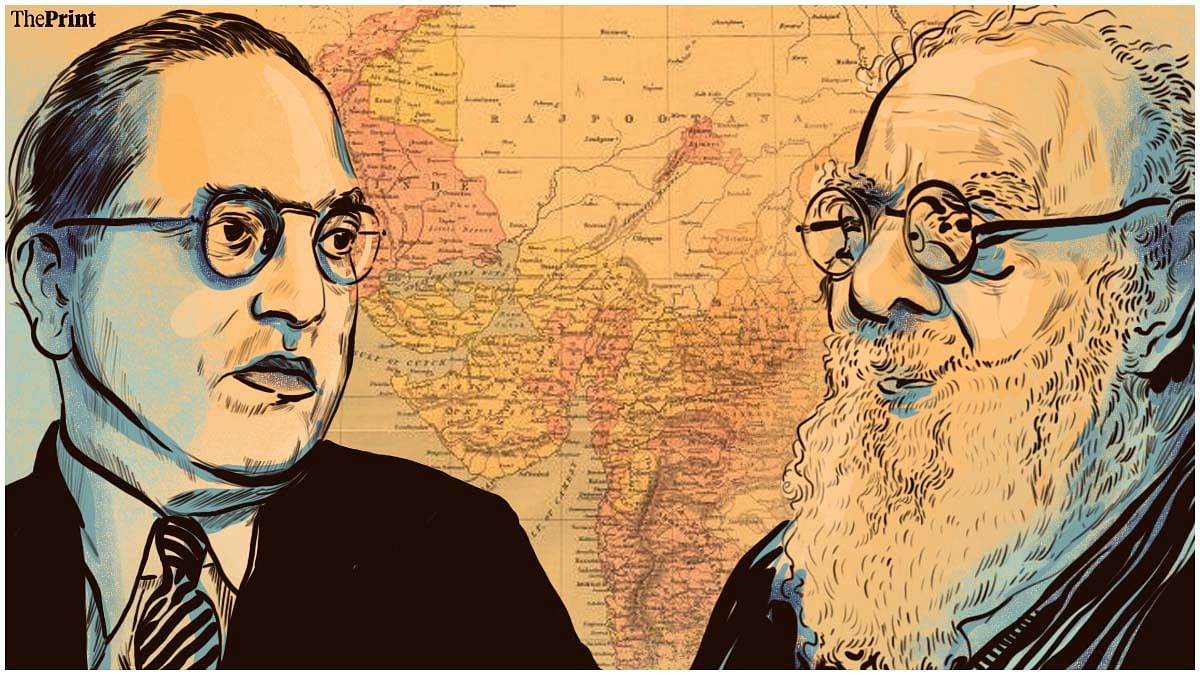

In 1952, Periyar declared that he would burn the constitution just like he had burnt other “impractical and harmful” religious texts. A year later, Ambedkar expressed a similar sentiment in front of the Rajya Sabha: “Sir, my friends tell me that I have made the Constitution. But I am quite prepared to say that I shall be the first person to burn it out”. What is important is here not the local meaning of the individual act of burning but the global power that it adds to the collective capacities of the citizenry. Focusing on the granularities of intention will culminate in the demonization of Periyar and Ambedkar as thoughtless individuals who are only intent upon destroying everything. However, when we look at their statements from the objective effects that it has upon the system of significations, it becomes clear that their very thoughtlessness serves to clear the path for building something new. Seceding from petrified patterns of thought requires the moment of dissolution, the assertion of annihilation. Consumption of sanctified objects can be carried out only through the disruptive chaos of thoughtlessness, which “is not some mystical disengagement from life,” but “an acute attentiveness to oneself and to the unconscious presuppositions of one’s thinking and speaking.” By declaring their intention to burn the constitution, Periyar and Ambedkar are demonstrating the earthliness of the document, its complete embeddedness in networks of social contestation. The constitution is not a divine structure that needs to be worshipped. Rather, it is a legal artefact whose relevance can be maintained only if it is attuned to the demands of the subalterns. Their concrete agency is the modality through which thoughts can be created, negated and developed in a free manner. Economic relations of property and power, not ideal categories of formal rights, constitute the ground for any just human project. Periyar labels as the procedure in which “words, writings, or sentences” are divested of their “exceptional meanings and philosophical discourses,” becoming reduced to “mere sentences” explicable through rationalist mechanisms.

Periyar foregrounded the materiality of thought in his response to the abstractionism of the naturalist notion of rights. Criticizing Bal Gangadhar Tilak, he wrote:

“Tilak claimed that Swaraj was his birthright, but since he was a varnashrama Brahmin, and since such men hold that others are inferior to Brahmins, this sentiment, in itself, becomes their birthright. It is, on this account, that Tilak was forced to use a term ‘Swaraj’ – useless for this purpose and dubious in its implications for practice – drawn from the field of politics to refer to his birthright. But we are not constrained to survive by deceiving others. Instead, we are intent on discovering humanity in its truest sense. Therefore, we maintain ‘self-respect is a man’s birthright’. We must realize that Swaraj is possible only where there is already a measure of self-respect and is otherwise not a discernible entity in itself.”

The naturalist notion of rights, with its idealistic view, results in the validation of hierarchies. It conceives rights as a theoretical ability to act that might be recognized and exercised, or not. This elevation of rights beyond social constraints localizes them as an innate capability, accessible mainly to a select few, namely upper-caste men. The sections of humanity that lie beyond the remit of rights do so on account of their inherent inferiorities. Periyar deconstructs this framework by equating rights with power. He comments: “What is prescribed as good conduct or bad conduct is to be measured by the strength and cleverness of the party that lays down the rules, and not by their intrinsic worth”. Rights of individual directly correspond to the reality of their actions, which encompass everything they are practically capable of doing and thinking within a specific set of circumstances. Insofar as a social formation emerges from the construction of interdependent connections between human beings, it is characterized by a blend of dependence and autonomy. Each individual asserts their distinctiveness amidst others, yet simultaneously relies on them to varying degrees. If an individual’s right is an expression of their capability, then it necessarily involves power dynamics – relationships of force whose fluctuations are determined by struggle.

Given the material context of forces, a subject’s identity is not an internal feature but the point at which relationships of cause and effect converge to determine our individual ratio of activity and passivity. An active subject is someone who decides how they relate to reality and can change or cancel that relationship if they want. If we can’t cancel our objective determinations, it does not belong to us. Becoming an active subject doesn’t involve the supervening role of a higher purpose. It simply means individuating oneself through the expropriation of one’s own conditions and the elimination of external causes. The subject’s activity is measured by “its ability to cause and determine a certain effect.” Against the backdrop of the hegemony possessed by theological abstractions, Periyar focuses on women as the subjective realm wherein the flows of power are laid bare. He elaborates:

“In all the world, chastity and love have been used to subordinate women and subject them to men’s control. Likewise, morality has been used to deceive and exploit the poor and the downtrodden. Chastity, Love, truth, justice, morals, etc., are all children of the same mother. They have all been used to make the proletariat to stick to a certain line of conduct for the ultimate benefit of clever and strong people. It is said that laws are all man-made and hence the subordinate position accorded to women. It can also be said that laws are all made by the strong and the mighty to subjugate the weak and the lowly.”

The counter-strategy to patriarchal sociality consists in a practice of militant equality. Periyar notes: “If a man has the right to kill women, a woman should also have the right to kill men. If there is a compulsion that women should fall at men’s feet, then men should also fall at women’s feet. This is equal rights for men and women.” A male-led agenda for the liberation of women “cannot give real liberation to women…Men’s pretense of respecting women and working for their liberation is nothing but a conspiracy to cheat women. Will rats be liberated by the efforts of cats? Will goats and cocks be liberated by foxes? Will the wealth of Indians increase because of the British? Will the non-Brahmins attain equality by the efforts of the Brahmins?” The stress on the self-activity of women indicates the centrality of expropriation, which is the only way in which property can become mine. Owning property isn’t a right; it’s a way to make yourself more powerful. Owning property empowers you because the ability to take things for yourself comes from within you, not from someone else’s permission. Legal, familial and religious institutions don’t give us the right to own things. The reason we can say something is ours is because we have the strength to protect it, whether on our own or with help from others.

Blumenfeld makes a distinction between freedom and ownness. The former “demands recognition from others,” making our identity dependent upon the goodwill of the other. The latter “can never be given by another, like a privilege or a right; it can only be expressed in one’s actions, like a disposition or power.” Instead of being an abstract moral idea imposed by the structure of recognition upon the subject, ownness is an activity that I undertake against oppressive constraints. It is contained in the process of consumption, which uses and abuses reality as one’s property, thus exploding it into a fluid multiplicity that does not need to tether itself to any permanent arrangement. The expropriation of external things allows the subject to create a world where it has the capacity to impact its surroundings, and negate any repressive solidity that threatens to delimit activity. In post-colonial India, the authoritarian stasis of communalism can be combated only through relational power for violation, consumption and expropriation that is brought about by the praxis of ownness. The activeness of the Indian ruling classes, their capacity to cause effects, is irreparably colored with the reproductive logic of a closed totality (neoliberal capitalism), which is dedicated to the conservation of the present and the blockage of an alternative future. Communism, in contrast, stands for the openness of self-determination, in which a profit-centric system is replaced with cooperative individuality. The latter is an arrangement wherein there “is no authentic self to realize, no essence to reveal or identity to defend. There is only the singular experience of consuming life to its end… Liberation and joy ultimately comes from breaking the inner compulsion to identify with anything at all, and instead, treating the world like property to be consumed in enjoyment with others.”

For Periyar, the demand for a sovereign “Dravidian” nation functioned not to express ethno-racial hatred towards “Aryans” but to create a utopia free from religion and caste. The Indian nation had to be made aware of the injustices that plagued its body politic. Just as destruction is an index of the ownness of property, “anti-national” criticism is indicative of the independence of the nation, its ability to be influenced by the self-determinative exercises of the masses. The nation is not a separate God lying above the material realities of the people; it is an instrument to be used and owned by them. If a nation has attained a life of its own and goes about arresting protestors, students, activists etc., it has become dead. To regenerate it, it is essential that we break its divine greatness and comprehend it as a historico-material entity whose existence depends on our own purposes.

Yanis Iqbal is studying at Aligarh Muslim University, India. He has published over 300 articles on social, political, economic and cultural issues. He is the author of the forthcoming book “Education in the Age of Neoliberal Dystopia”. He can be contacted at yanisiqbal@gmail.com.

0 Response to "Deconstructive Praxis and the Politics of Independence"

Post a Comment

Kalimpong News is a non-profit online News of Kalimpong Press Club managed by KalimNews.

Please be decent while commenting and register yourself with your email id.

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.