No one wants to talk about rapes in Manipur. There’s a silence at the heart of the violence

In India, communal rioting includes revenge attacks based on fake news – from Muzaffarnagar riots to Delhi riots. Manipur's ethnic clashes witnessed 'revenge rape' following a false claim.

|

| The medical student who was abused in Imphal recovering in a hospital in Churachandpur | Photo: Suraj Singh Bisht/ThePrint |

The woman in the photo was later confirmed as Aayushi Chaudhary from Delhi who had been murdered by her parents in November 2022 – she was not a Manipur nursing student. But by then, the fake news had unleashed a new, deadly cycle of reprisal violence on Kuki tribal women allegedly by Meitei mobs. Over 150 people have been killed, 300 injured and more than 40,000 displaced during the two months of unprecedented ethnic clashes that broke out between Kukis and Meiteis. But the spate of sexual violence against women is the least talked about wound in the Manipur ethnic mob attacks – a testimony to the social stigma and culture of silence around rapes that Indian women still battle.

Inebriated men, some as young as 15 years old, dragged a Kuki woman in her 40s and a teenager to a paddy field near Toubul village in Bishnupur district on 4 May and raped them. As their ordeal was on, the men screamed, “We will do to you what your men did to our women.” For them, this was retribution.

“It was all because of a fake news. The men were saying ‘this is revenge for the Churachandpur case’,” said the woman to ThePrint, sitting in a vacant room at the relief camp in Churachandpur, pausing to take sips of water. She spoke for over two hours, narrating the ordeal in vivid details.

Still numb and in shock, she is trying to rebuild her life and planning to move out of the relief camp.

“I can’t make sense of anything. The men were under the influence of alcohol. I don’t think they knew what they were doing,” she said.

In the ongoing ethnic riots in the hill state, angry mobs used women’s bodies to take vengeance for a crime that was never committed. But amid widespread lynchings, burning, looting, and ethnic fault lines that have divided Manipur into partitioned villages, cities, streets and neighbourhoods, a shroud of hushed silence is stopping women from speaking about the horrific sexual atrocities committed against them.

None of the women, including the 40-year-old rape survivor, have filed a police complaint yet.

Fighting shame, humiliation and stigma of sexual crimes, Manipur-based lawyers and human rights activists said these crimes may be buried forever.

“If the women don’t report the crime, these will mostly be forgotten in the tribal community. We never talk about these things,” says Kai Suanta, a lawyer from Churachandpur.

The women aren’t speaking, but there are eyewitnesses, first-responders, and caregivers at the shelters who know about the sexual assaults.

Rape is used as an instrument of violence during riots and conflict situations across the world. It is also recognised by the Genocide Convention international treaty.

“Bodies of women are where the valour and the pride of the community lies. And one group crushes it by raping the women of the other community,” said Suroor Mander, a lawyer who worked on sexual violence on women during the 2002 Gujarat and 2020 Delhi riots. If the police do register FIRs on rape in communal riots, they mention nameless, faceless ‘mobs’.

|

| The 40-year-old woman who was allegedly raped in a paddy field is now living in a relief camp in Churachandpur | Photo: Suraj Singh Bisht/ThePrint |

In Manipur, ThePrint spoke to survivors and volunteers at relief camps to learn about at least six cases of rape of Kuki women, including the 40-year-old and teenager from Bishnupur. The medical report of an 18-year-old survivor from Kangpokpi confirms rape, but she too has not filed an FIR. A 22-year-old medical student has denied to ThePrint that she was raped. Families of two women, Alice and Mary (names changed), who worked at a car wash shop in Imphal, have filed FIRs alleging rape and murder of their daughters.

The police say they have also heard about the rapes. But add that they have not received any complaint so far.

“There are allegations of rape from both communities (Meiteis and Kukis), but no case has been registered so far. The consent of the victim is required and the police cannot take suo moto action,” said a senior officer who did not want to be named.

More than two months since the attack, survivors have blended among thousands of displaced people at the various relief camps. And their sexual trauma has dissolved into the countless stories of horrific mob attacks.

Also read: One thing was distinctly rotten about 2002 Gujarat riots: use of rape as a form of terror

Fake news led to rapes

Within 48 hours of the clashes breaking out in Manipur and the false claim spreading on social media, the police busted the fake news.

On 5 May, then-Director General of Police P Doungel was quick to clarify that no rape of Meitei women took place in Churachandpur. The father of the purported nursing student referred to in the viral claim gave a statement to Impact TV, a local broadcast network, that his daughter was unharmed.

But the frenzy on social media continued to instigate the mob.

On 5 May evening, fear gripped Alice and Mary, friends in their 20s. They hid under a bed at their car wash shop from a mob looking for Kuki women, but couldn’t stay hidden for long. For two hours, their helpless co-workers heard them scream and plead the seven men who had locked themselves in the room. The women were later found dead, their blood and hair splattered all over the room.

“People at the car wash told us that the men did wrong things inside the locked room. My sister and Mary were screaming,” said Alice’s elder sister.

Hoineilhing Sitlhou, who teaches sociology at the University of Hyderabad, began digging into cases of violence against women in Manipur. Eyewitnesses reportedly mentioned to victims’ parents that women were screaming, ‘please let me go’, ‘don’t touch me’, ‘please leave me alone’ — which hinted that they were being sexually assaulted.

|

| Kuki women in Churachandpur protesting outside the district administration office in June (Photo credit: Sonal Matharu) |

The shame and humiliation of rape isn’t just limited to the woman’s trauma of having her bodily integrity defiled, but becomes associated to the entire community.

“Sometimes the woman’s own family and community, who should be the source of her support, turn around and see her as ‘polluted’,” says a human rights activist who requested anonymity as they have received threats.

Rumours and fake forwards are playing an increasingly sinister role in stoking violence around the world – from the US elections to the Ukraine war. In India, communal rioting includes many revenge attacks based on fake news – from Muzaffarnagar riots to Delhi riots.

“Fake news during riots fuels anger. It acts as a spark in a dry wood forest. It will lead to a forest fire. And a raging one on top of it,” said lawyer Mander.

When Muzaffarnagar riots broke out in 2013, an old video of a fight between two men was circulated on Facebook with a false claim that one of them had tried to molest the other’s sister, explains Mander.

“That is not a true story. In fact, the girl has officially denied it on multiple occasions. Falsehood and fake stories create anger,” she says.

It also instigates the other community to take up arms to defend themselves.

“A fear is created within the community about the safety of women which then antagonises them to become defensive and act out. It then continuously fuels and perpetuates violence. More violence occurs and the state suppresses it by again oppressing women and women’s bodies,” adds Mander.

|

| Kuki villagers watch from a distance as a Meitei village goes up in flames on the border of Bishnupur and Churachandpur | Photo: Suraj Singh Bisht/ThePrint |

Violence continued unchecked

Meanwhile, sexual violence against women extended beyond the initial days of the riots when misinformation became alibis to torture women.

On May 15 evening, an 18-year-old Kuki college dropout, who had taken shelter at a Muslim family’s house in Imphal, was abducted from outside an ATM by men wearing black t-shirts who came in two cars – a white Bolero and a purple swift. Since the conflict started, men in black are being referred to men from Arambai Tenggol, an armed Meitei group. Black clothes are their uniform.

In a city under curfew, the two vehicles managed to drive around with the girl, who was blindfolded and tied.

“She was with four men who were in the Bolero and the other car left. She was beaten and assaulted inside the vehicle,” said a volunteer at a relief camp in Kangpokpi to whom the 18-year-old narrated her story.

The men drove her to a hill and when the girl refused their sexual favours, they beat her up with the butts of their guns after which she fell unconscious, says the volunteer. When she regained consciousness, she escaped by rolling down the hill and taking help from a Muslim auto driver who drove her to safety.

“Three days later, when the girl reached our relief camp, her face was covered with scars and she could not even speak. There was a huge cut on her eyebrow, her lips were blue and her eyes were totally red. Just by looking at her, I got goosebumps and I feel so uncomfortable and uneasy recalling that moment,” said the volunteer.

The girl’s family was reluctant to talk to the volunteers as the girl had been threatened by her abductors.

“The men said that her life is still in their hands and she should neither report this to the police nor talk to the media,” said the volunteer.

But when the girl’s condition worsened and she started bleeding, she was taken to a hospital in the neighbouring state, Nagaland. Her medical reports, which ThePrint has accessed, confirm rape and sexual assault.

“Assault and rape on 15th May during the Manipur tribal clash,” the report notes.

But the family has not gone to the police about this either.

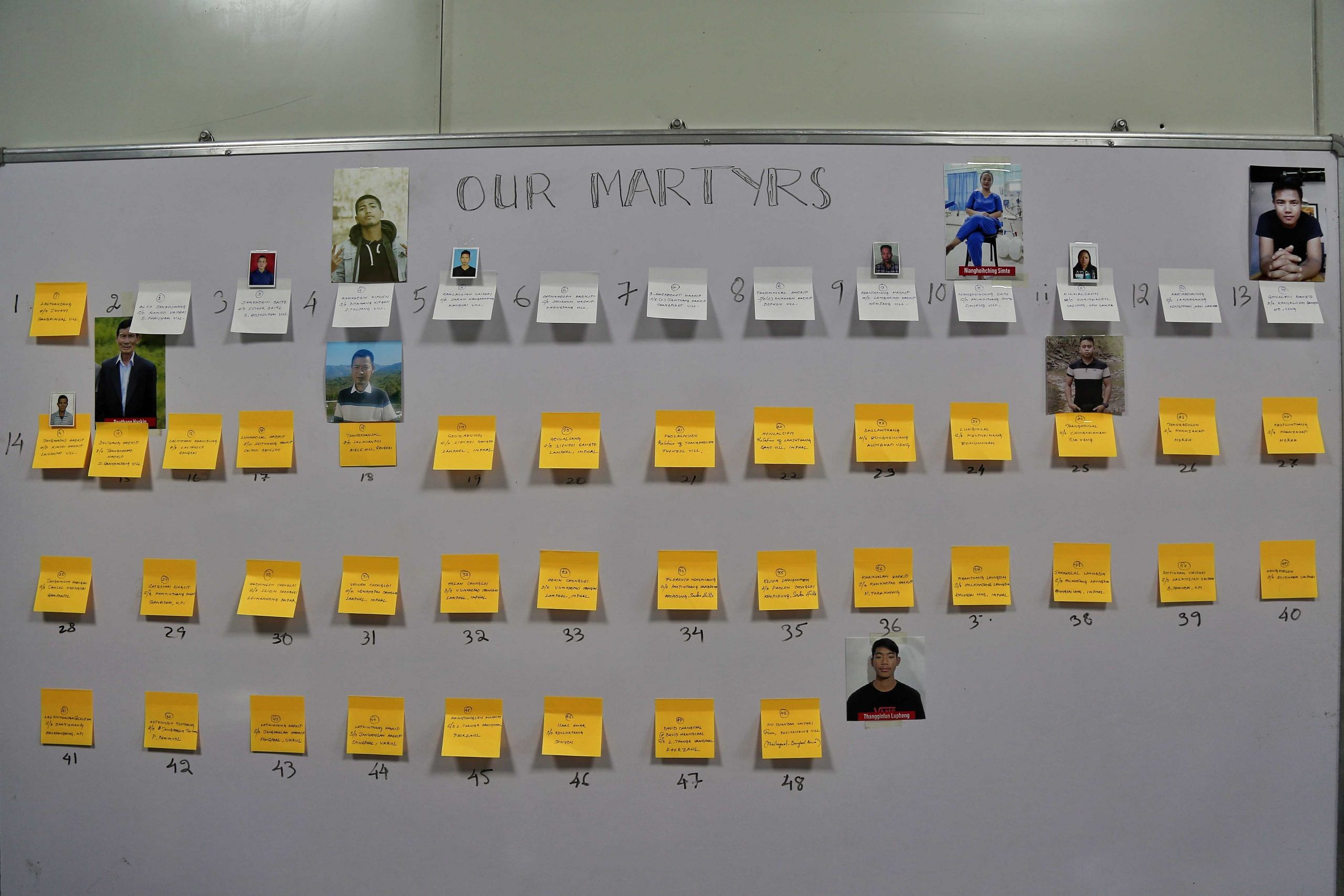

At the makeshift office of ITLF in Churachandpur, a list of all Kukis who have died since May 3 has been put up. The list keeps getting bigger daily | Photo: Suraj Singh Bisht/ThePrint

|

| At the makeshift office of ITLF in Churachandpur, a list of all Kukis who have died since May 3 has been put up. The list keeps getting bigger daily | Photo: Suraj Singh Bisht/ThePrint |

What can be done

A three-member team of National Federation of Indian Women (NFIW), women’s wing of Communist Party of India, headed by general secretary Annie Raja, visited Manipur from last month (June 28 – July 1) and met women who were alleged victims of sexual violence.

Without disclosing which community the aggrieved women belonged to, Raja told ThePrint that the trauma of the crime runs deep and they have little support or assistance.

“Women are hesitant to reveal sharing what they faced. A woman started to explain how she was harassed, but stopped right before describing the story of rape and started crying. We did not insist that she should open up as this would mean punishing her again,” said Raja.

Sitlhou, who belongs to Manipur, explains that there is a perception that the tribal societies are egalitarian, but patriarchy runs deep in the tribal communities as well.

“The stigma around rape has to do with the woman’s prospect of marriage. Families might not accept women who have been, to put it this way, ‘defiled’,” said Sitlhou.

In times of conflict, the environment is also not conducive for women to come forward and report the crime. Often, it is the men who become the spokespersons of a community and its tragedies during rioting.

“When women are displaced, their primary concern at that time is to find a safe space for themselves and their family. They don’t have the wherewithal or even the mental ability to think of going and reporting rape,” says Aparna Bhat, senior lawyer working on crimes against women.

Reporting on the crime happens after the women find a safe space, she adds, perhaps much later.

Experts, however, suggest that the National Commission for Women or human rights commission can investigate the cases. Police can take suo moto action based on media reports or the government can also form a commission of inquiry.

Lives cut short

“My sister was happiest when she was in front of the mirror,” said Alice’s sister, breathing heavily on the phone as memories of her sister and her tragic end overwhelmed her. Alice was only 24 years old and wanted to be a beautician.

In the room where the two women were abused, hair was spread all around. Mary’s long beautiful hair was pulled and chopped during the assault, eyewitnesses told her sister.

The FIRs filed by their parents have not witnessed any development so far. The families have also not received their daughters’ bodies, which are allegedly kept in the morgue at the Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Medical Sciences (JNIMS) hospital in Imphal.

The teenager who was raped in the paddy field has been relocated to an unknown location in Chandel district, while the 18-year-old has moved to a new relief camp with her family.

Meanwhile, in Churachandpur, the 22-year-old medical student who was brutally beaten by a mob on 4 May in Imphal, is slowly recovering from her injuries. Her eyes welled up when she recalled that tragic night where she was left to die. Men punched her face, stood on her body, and broke three of her front teeth. She regained consciousness at the emergency room at JNIMS hospital in Imphal.

Her prescription from JNIMS, where she was first taken, is written on a plain A4 sheet instead of a hospital letterhead. Though she was admitted as a victim of violence, she was not tested for sexual assault. She was diagnosed with headache, pain and swelling on face and eyes with three front teeth missing. For treatment, she was prescribed antibiotics, eyedrops, and pain killers.

When the mob was thrashing, the women who were a part of it yelled, “rape her, kill her, burn her. Do to her what her people did to our women.” They were referring to the same fake news of the rape and killing of the Meitei nursing student in Churachandpur.

Volunteers at the relief camp narrated the medical student’s case as one of the most gruesome they have come across. But when ThePrint met her last month, recovering in Churachandpur district hospital, she denied that she was raped.

“The mob was screaming, ‘rape her’. But they did not do it,” she says with a straight face.

The Print’s Ananya Bhardwaj contributed to this story from Imphal.

0 Response to "No one wants to talk about rapes in Manipur. There’s a silence at the heart of the violence"

Post a Comment

Disclaimer Note:

The views expressed in the articles published here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position, or perspective of Kalimpong News or KalimNews. Kalimpong News and KalimNews disclaim all liability for the published or posted articles, news, and information and assume no responsibility for the accuracy or validity of the content.

Kalimpong News is a non-profit online news platform managed by KalimNews and operated under the Kalimpong Press Club.

Comment Policy:

We encourage respectful and constructive discussions. Please ensure decency while commenting and register with your email ID to participate.

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.