One year since lockdown 1.0: Share in workforce already falling, Covid-19 job losses hit women harder

Don't Miss

From Gurugram to Srirangapatna, the Covid-19 pandemic and the lockdown-induced economic distress deepened a structural problem that India’s labour market was already witnessing -- participation of women in the workforce.

A year ago, migrant workers leave New Delhi for their home states due to the lockdown imposed to curb the spread of Covid-19. (Express Photo/File)

Aanchal Magazine , Pranav Mukul , Anil Sasi | Manesar, New Delhi | March 24, 2021: For 28 years, Munni Devi walked from home to the Welspun Polybuttons Pvt Ltd factory on Gurugram’s Behrampur road where she headed the button assembly process on the shopfloor. Today, the 54-year-old does the same walk via her factory but to a different destination: a protest site at the Gurugram mini-Secretariat.

She is among the 200 employees laid off after the factory closed three months into the lockdown that marks a year tomorrow. Out of a job since last July, Munni’s family struggles to pay rent, cuts corners to buy medicine for her physically challenged grandson. Of the three working members in her household of five adults who lost their jobs since then, two are women.

Far away from her, at Euro Clothing Company’s factory in Karnataka’s Srirangapatna, Shobha S, a mother of two and the breadwinner in her family, was among the nearly 1,300 workers laid off in June. Nearly all the workers fired at this unit of Gokaldas Exports, which counted H&M as among its suppliers, were women like Shobha.

From Gurugram to Srirangapatna, the Covid-19 pandemic and the lockdown-induced economic distress deepened a structural problem that India’s labour market was already witnessing — participation of women in the workforce.

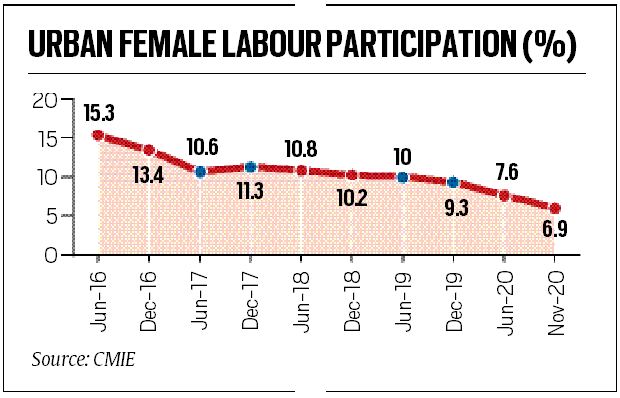

With each passing year, fewer women were seeking work or were simply falling out of the workforce. From 16.4% in May-August of 2016, the female labour participation rate (employed women as a proportion of all women of working age) fell consistently after the demonetisation shock to stabilise at around 11% between mid-2018 and early 2020, according to estimates of Mumbai-based Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE).

The pandemic, by most accounts, dealt this a hammer blow, pushing this number to around 9 per cent.

Women, according to the CMIE, accounted for 10.7% of the workforce in 2019-20, but they accounted for 13.9% of the job losses in April 2020 — the first month of the lockdown shock. By November 2020, while men recovered most of their lost jobs, women were less fortunate. CMIE estimates that 49% of the total job losses by November 2020 were of women.

Official data on employment by gender is sketchy. Information on the number of women whose enterprises had to close down during the pandemic is “not maintained” in Ministries such as the one that handles Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises or MSME. But a study by Khadi and Village Industries Commission to assess the impact of the pandemic on micro units, including women-run micro units, set up under the Prime Minister’s Employment Generation Programme is telling: as high as 88% of the beneficiaries of the PMEGP scheme said they were “negatively affected” by the pandemic.

Queries sent by The Indian Express to Gokaldas Exports and Welspun Group went unanswered but interviews of several women workers, employers, experts and officials show three key reasons for working women to face the bigger brunt of the pandemic distress as compared to men.

One, sectors such as textiles and contact service providers which employ more women than men got hit the hardest. Second, given that schools were shut down and the family unit was under pressure, many women workers, once they lost their jobs, quickly slid back to their full-time role as home-makers and care-givers as their male counterparts looked for re-instatement.

Third, lack of transport was one key factor, many women said. In the initial months after the easing of the lockdown, many factories and companies did not provide conveyance for them – this was a stronger deterrent for women than men.

“There are issues specific to some sectors. Retail has been affected, resulting in (an impact) to sectors such as garment manufacturing,” Labour Secretary Apurva Chandra told The Indian Express. He said that given their high numbers of women in the garment trade, which was impacted by the downturn in the retail sectors because of sluggish demand, women have been hard hit.

The government challenges the CMIE numbers, claiming its surveys peg the share of women in the workforce nearly 10 percentage points higher than CMIE’s 11 per cent, pre-pandemic.

Not quite, says CMIE Managing Director and CEO Mahesh Vyas. “Every time there’s an economic shock, women and younger people suffer the most. And it takes a long time to recover from this shock,” he said.

“So after demonetisation, it took 2.5-3 years before women started coming back into the labour force. As soon as that went away, Covid came as another shock…Because of the weakness of women’s participation in the labour market, they were hit the most. If you have a weak muscle, that’s the one that starts paining when there’s a shock.”

Source: Periodic Labour Force Survey, MoSPI

How weak that muscle is confirmed by official quarterly urban employment statistics: unemployment rate for women increased to 21.2% in April-June 2020, up from 11.3% in the corresponding period a year ago and 10.5% in the previous quarter.

For urban males, it was at 20.8% in April-June as against 8.3% in April-June 2019 and 8.7% in the previous January-March quarter.

According to data from the ILO, most of the working hours lost during the pandemic was because of workers asked to put in fewer hours per week or to not work at all rather than persons moving into unemployment or outside the labour force. The crisis was more pronounced for women than men in most economies.

One year since India's lockdown |How many cases and deaths did it prevent?

The distress is visible at the bottom of the value chain as well. At Sarhali Kalan village, 50 km outside Amritsar in Punjab’s Tarn Taran district, 32-year-old Devi Kumari has been without work for over four months. Kumari relies on MGNREGA wages to manage the finances of a three-member household by cutting down on non-discretionary spends such as food and medicines.

“I work as a cleaner at the village water tank. None of the labourers, including me, got the assured 100 days of work under MNREGA. Last I worked was more than four months ago,” Kumari told The Indian Express. In the absence of a regular income, she turns to odd-jobs in farms.

The findings of the Azim Premji University Livelihoods Survey for April-May 2020 underlined the glaring gender gap in job losses. Around 70% of males and females – of migrants returning home — lost their jobs during lockdown of which about 22% percent of women were not able to find work in the post-lockdown period, while the corresponding number for men stood at 15%.

For Munni, this is of little consolation. “Some dues were settled but we were not given any explanation by the company for why they ended our service contract. At this age, no one is willing to hire me, so for the last one year I have been unemployed,” she said.

With her colleagues Savita Sharma, Ram Ratni, Lakshmi Devi and Omvati, who have all served years in the Gurugram Welspun unit, Munni appealed to her employer. “We’re willing to work at a lower salary. Getting our job back is important”.

That’s unlikely to cut much ice, given that the unit has not reopened since the lockdown. Trade unions took up their case with the region’s labour officials, proceedings of which have now been shifted to Chandigarh’s labour court, said Anil Pawar of All India Trade Union Congress, Haryana.

In Srirangapatna, there’s some headway. Jayaram Ramaiah, Legal Adviser, Garments and Textile Workers Union said after the layoff was announced on June 6, workers sat outside the factory for nearly 45-50 days.

“Finally, workers resigned and the company paid some money — additional to their compensation. After this, we continued our struggle. We took help from international organisations and put pressure on the brand, which put the pressure on Gokaldas Exports, and finally on February 1 this year, they agreed to take back the workers with continued service. Now they are beginning to provide some jobs in Mysore,” he said.

0 Response to "One year since lockdown 1.0: Share in workforce already falling, Covid-19 job losses hit women harder"

Post a Comment

Disclaimer Note:

The views expressed in the articles published here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position, or perspective of Kalimpong News or KalimNews. Kalimpong News and KalimNews disclaim all liability for the published or posted articles, news, and information and assume no responsibility for the accuracy or validity of the content.

Kalimpong News is a non-profit online news platform managed by KalimNews and operated under the Kalimpong Press Club.

Comment Policy:

We encourage respectful and constructive discussions. Please ensure decency while commenting and register with your email ID to participate.

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.