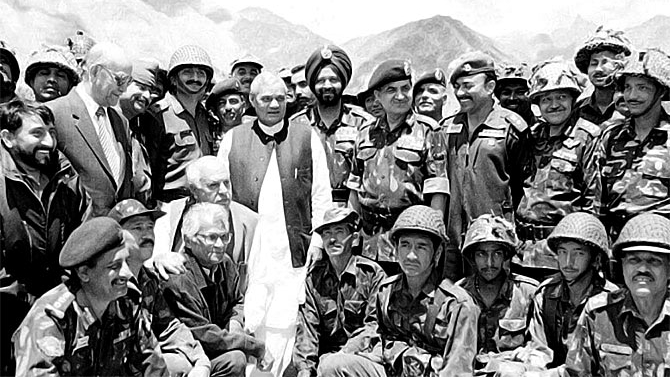

Kargil: the drama behind the scenes - Vajpayee’s ex-aide shares his experience of shadowing the former PM during one of the most challenging times India faced

Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s ex-aide shares his experience of shadowing the former PM during one of the most challenging times India faced

To illustrate how ill-informed, or inadequately informed, we still were in the last days of May, just when Vajpayee was telling India that the situation was more serious than previously expected, we were offering the Mujahideen a safe passage. This was not because India was uncertain and wanted an early end to conflict, but because it was expected that the Mujahideen would not have the stomach for a long fight. Thus, while on the one hand, it was realized that the situation serious, it was still unclear as to how serious it would get. Unfortunately, the Pakistanis saw it as a sign of our innate ‘defensiveness’, and the point of providing a safe passage was rightly not pursued by us. Slowly, the tide would change as the army and the air force would get their act together by marshalling their resources and adjusting the battle plans to suit the geography of the high-altitude war they were fighting.

The pendulum started swinging our way not just because of the battlefield action but, more importantly, because of an intelligence breakthrough that suddenly galvanized India and made the Pakistan Army look devious. Arvind Dave, the RAW chief, came up with two telephonic recordings between the Pakistan Army chief, General Pervez Musharraf, and his chief of the general staff, Lt Gen. Mohammed Aziz. Brajesh Mishra and Dave brought the tape to Vajpayee, and we heard the conversation. There was stunned silence. It was clear that the Pakistan Army was involved, with the Mujahideen playing a minor role, if any. The Indian Air Force aircraft had been brought down by the Pakistan Army, though they got the Mujahideen to claim it. Musharraf was not happy that the helicopter had crashed on the Indian side of the LoC.

Lt Gen. Aziz then said something that indicated his correct understanding of India’s resolve to up the ante if things did not go its way. He told Musharraf that a few Indian bombs had fallen on the Pakistani side of the LoC, and that this was deliberate. They did not hit any targets but the point of the strike, as understood by the Pakistanis, was that India could hit targets across the LoC. Though Lt Gen. Aziz mentioned that Nawaz Sharif had been briefed at a meeting on 27 May at his office, it was unclear how much the latter knew. The Pakistan Army’s stand, which it wanted their foreign office to propagate, was that while they were located within their side of the LoC, there might have been certain border crossovers due to lack of clarity in the line’s actual demarcation.

The Pakistan Army was happy that the Kashmir issue was being internationalized, with the UN secretary-general, Kofi Annan, calling on both sides to exercise restraint. The Pakistan Army was also clear that in his forthcoming negotiations with India, Pakistani foreign minister, Sartaj Aziz, should not accept a ceasefire, since that would allow the Indian Army to use the Srinagar–Drass–Kargil highway to move men and material. It was then expected that the two foreign ministers would meet on 30 May. But the meeting was ultimately held on 12 June, by which time a lot of water had already flowed down the Indus.

Though the CCS was made aware of them, the Musharraf-Aziz tapes were not circulated outside this small group initially. Vajpayee wanted to find a peaceful solution; or to put it differently, he wanted to give Nawaz Sharif a chance to bring the conflict to an early end. R.K. Mishra — a veteran journalist and editor of the CPI-leaning Patriot and Link, former Congress MP and head of the Reliance-funded think tank, Observer Research Foundation — was drafted to activate back-channel diplomacy with Pakistan. His interlocutor on the other side was the veteran diplomat Niaz Naik. While the war was on, Mishra made three trips to Pakistan to meet Sharif, with Naik making one trip to India. Mishra carried the tapes and transcripts to Sharif. As Mishra reported to Vajpayee, Sharif had turned ashen while listening to them. Was it because he had been caught red-handed? Or was it because he wasn’t fully aware of the extent of the audacity, and adventurism, of Gen. Musharraf?

Subsequent evidence suggests that Sharif was not consulted or informed about Operation ‘Koh-i-Paima’, under which troops of the NLI were inducted into vacated Indian Army posts; and when Sharif was finally briefed during the first meeting about the operation, the army had refrained from giving him the entire picture. However, his foreign minister, Sartaj Aziz, and defence secretary, Lt Gen. Iftikhar Ali Khan, had caught on and advised Sharif to caution the army, at which point, the army won him over by saying that post the success of their operation, Sharif would be remembered as the ‘Victor of Kashmir’.

However, Sharif’s position was a tenuous one, and in a later meeting, he indicated to Mishra that they should take a walk in the garden, obviously suspecting that his own house was tapped. When Mishra reported this to Vajpayee, the latter took this as an indication that Sharif was more a prisoner of circumstances than anything else. So Vajpayee continued to pin his hopes on Sharif, counting on his help in de-escalating the situation between the two nuclear powers. Vajpayee must have spoken to Sharif 5–6 times during the one and a half month period from mid-May to 4 July, when the Pakistani PM publicly committed to President Clinton that Pakistan would withdraw its forces to its side of the LoC.

One of these calls was made in mid-June, from Srinagar, after Vajpayee had made a visit to the town of Kargil. Sporadic Pakistani bombardment was on, and we saw from the helipad across the river some shells hitting areas near the highway. On his arrival in Srinagar, Vajpayee asked me to connect him to Sharif. My small team and I tried, but we just could not get through. Then one of the local officers present informed us that dialling Pakistan (+92) from Jammu and Kashmir was barred. The telecom authorities were told to open the facility for a short while, so that the two prime ministers could talk.

Back-channel diplomacy, which generally means using non-officials in developing basic common understanding before formal talks could be held, was not without its peculiar challenges. How do we send across R.K. Mishra at short notice with the tapes and without airport security at either end getting too nosy about what he was carrying? The answer was to make him accompany Vivek Katju, who continued as our point person on Pakistan. Since the legal fiction of Pakistan not being in the picture anywhere in Kargil was accepted, almost till the end of the conflict, normal communications between the two countries continued. Hence Vivek’s tour to Pakistan, with diplomatic bags immune to checks, was nothing unusual.

Later, this pretence of normalcy was not required as long as the Mishra–Naik talks were not publicized. It also had its humorous interludes. Once, Mishra rang up very agitated and said that he was suspicious about an Ambassador car, with a few occupants, parked near his house in Vasant Vihar. Since he was carrying out a sensitive assignment, he feared the worst. I was asked to have it checked. The Delhi Police promptly moved in and the car and its occupants were removed. No sooner had this happened than an angry Shyamal Datta rang me up on the government’s secured phone system, complaining that some IB personnel, who were keeping a watch on somebody else, had been removed by Delhi Police on instructions from the PMO!

Excerpted with permission from the publisher

0 Response to "Kargil: the drama behind the scenes - Vajpayee’s ex-aide shares his experience of shadowing the former PM during one of the most challenging times India faced"

Post a Comment

Kalimpong News is a non-profit online News of Kalimpong Press Club managed by KalimNews.

Please be decent while commenting and register yourself with your email id.

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.